A Message from the Chair

Historians spend a lot of time thinking about the ways that today’s world echoes the past, both in the context of our own lives and far longer spans. My colleagues who work on Medieval and Renaissance Europe split on whether our compatriots will handle the corona virus much like the bubonic plague—Joel Mokyr predicts that scientific rationality will help but Dyan Elliott is less sanguine, showing that temperament makes a difference as well as expertise! Certainly, public culture and work space have both been radically redefined in the last few weeks and these restrictions will go on for months. It is hard to know how best to respond except that living through a “world-gone-mad” moment will definitely give me insights into the world of my historical actors. And I plan to look to them for coping ideas as well.

Before this happened I was thinking in less dramatic terms about the passing of time, moved by two events from the last six months. First, the chair of the Northwestern Homecoming alumni event this fall, Richard Briggs, who graduated as a History major fifty years ago, asked us to organize a short program on the changes from History at NU in 1969-70 to History today.

What are those changes? First of all, the department has more than doubled in size in the last fifty years, going from 21 to 44 tenure-track faculty. This occurred while Northwestern as a whole has risen from its status as a good regional school to one with a stellar national reputation. 1983, the year that rankings really started to become public knowledge, placed Northwestern at number 17. By 1990 our status had climbed to 14 where it stayed for quite some time. In 2019 US and World News Report raised our ranking to 9th best school in the nation.

Of course the range of topics we teach has also shifted a great deal: Most notably, our coverage of the world beyond Western Europe and the United States has expanded. But we also offer classes in whole new fields that did not exist in 1969 —in Fall quarter alone we fielded American prisons, Korean Diaspora, Arabian Intellectuals, and the History of the Human Body.

We changed in part because it is fun to learn new things, and the freedom to do so on the job is one of the best perks of being a professor. But we also collectively shifted our focus because the students themselves no longer overwhelmingly think of themselves as “of European stock.” And while many members of the academy believed in the existence of a unified “Western Civilization” separate from the rest of the globe in 1969, none of us today is unaware of the long histories of diversity within “the West” and profound forms of interaction with “the non-West.”

But despite the many ways in which History at Northwestern has changed in fifty years, I was surprised to discover the considerable extent to which Northwestern faculty in residence in 1969 already managed to pioneer a number of fields that I had incorrectly thought were newly important today. Of course African history has long been a department staple, but the impact of one individual was truly profound: when John Rowe retired, I learned that he had trained 63 graduate students, meaning that he is still shaping the field even though he left the profession decades ago.

The NU History Department also boasted one of the pioneers of global history in 1969, Leften Stavrianos. Himself Greek-Canadian, Stavrianos noticed how much the world has always been connected—because people who come from peripheral places always have a better perspective on this issue than do people at centers of power. I also note a different acknowledgement of power in the adjusted title of his major book, the early editions of which were called A Global History of Man (1962), later simplified and amplified to A Global History. Another NU scholar took a global perspective on the history of racial thinking, although his most famous book on the subject came after he left NU for Stanford. That was George Frederickson, author of The Black Image in the White Mind (1971) and Racism: A Short History (2002).

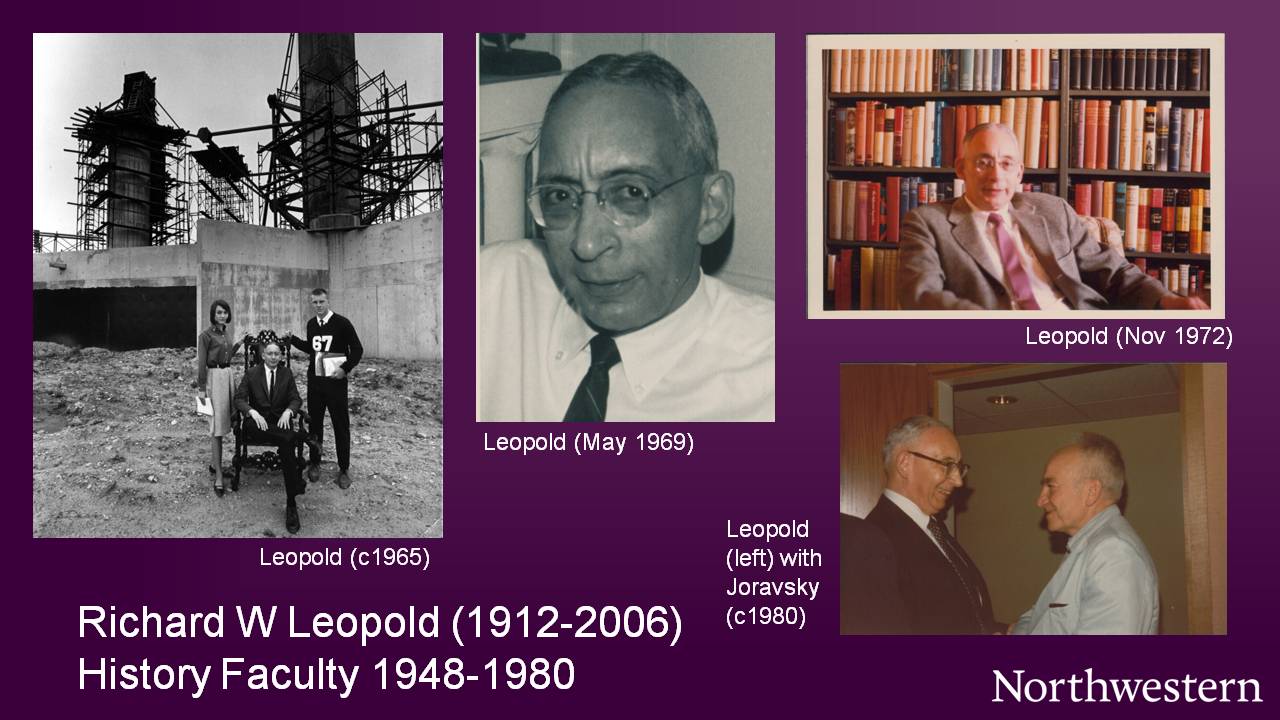

We also had a pioneer in Narrative History: Lacey Baldwin Smith, who wrote best-sellers on Tudor-Stuart England. (He also ate exactly the same lunch every day: A thin slice of baloney sandwiched between two slices of white bread, a bottle of beer, and a very large Hershey’s bar.) Together with Richard Leopold, he was also a legendarily good teacher.

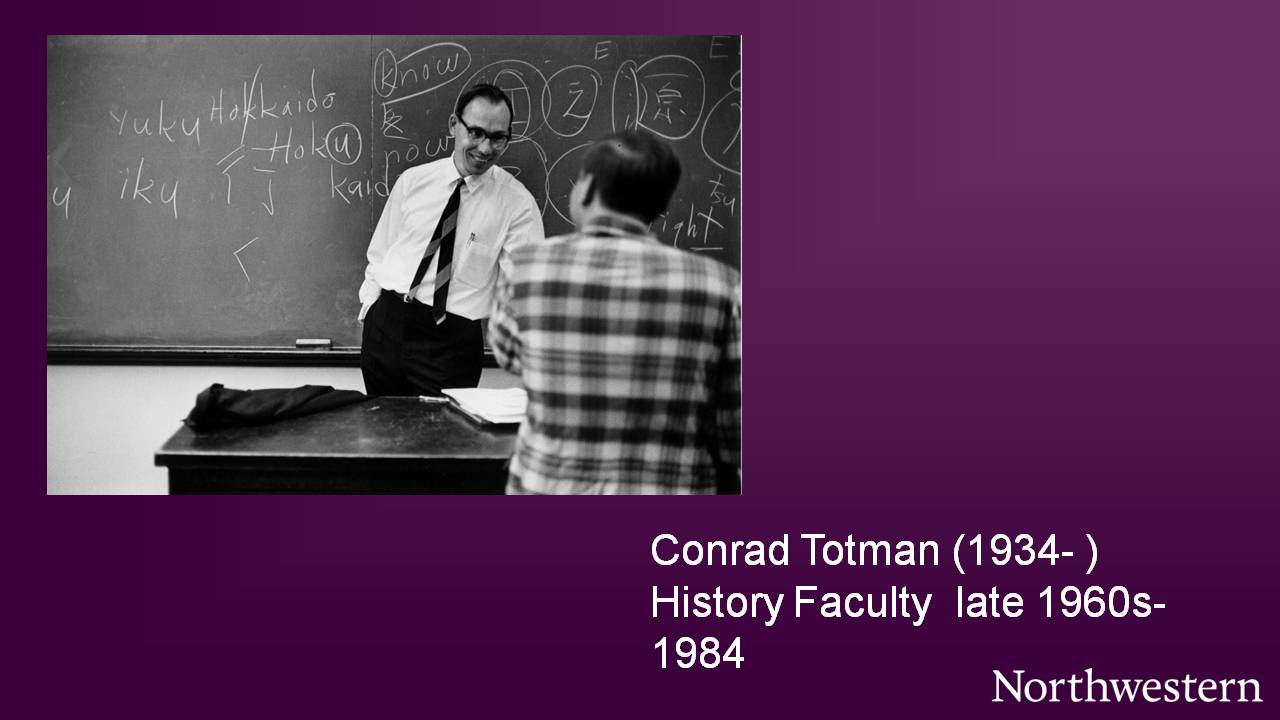

History of Science, another very strong field at NU today, already was so in 1969 when David Joravsky held down the fort. He would soon be joined by Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs who was here by 1977 and left in 1991. Jo was the first woman to achieve tenure in the department. Conrad Totman another scholar at NU in 1969, and the man who held the position I occupy now, published a history of forests and forest management in Japan that is still widely read in the field of environmental history today.

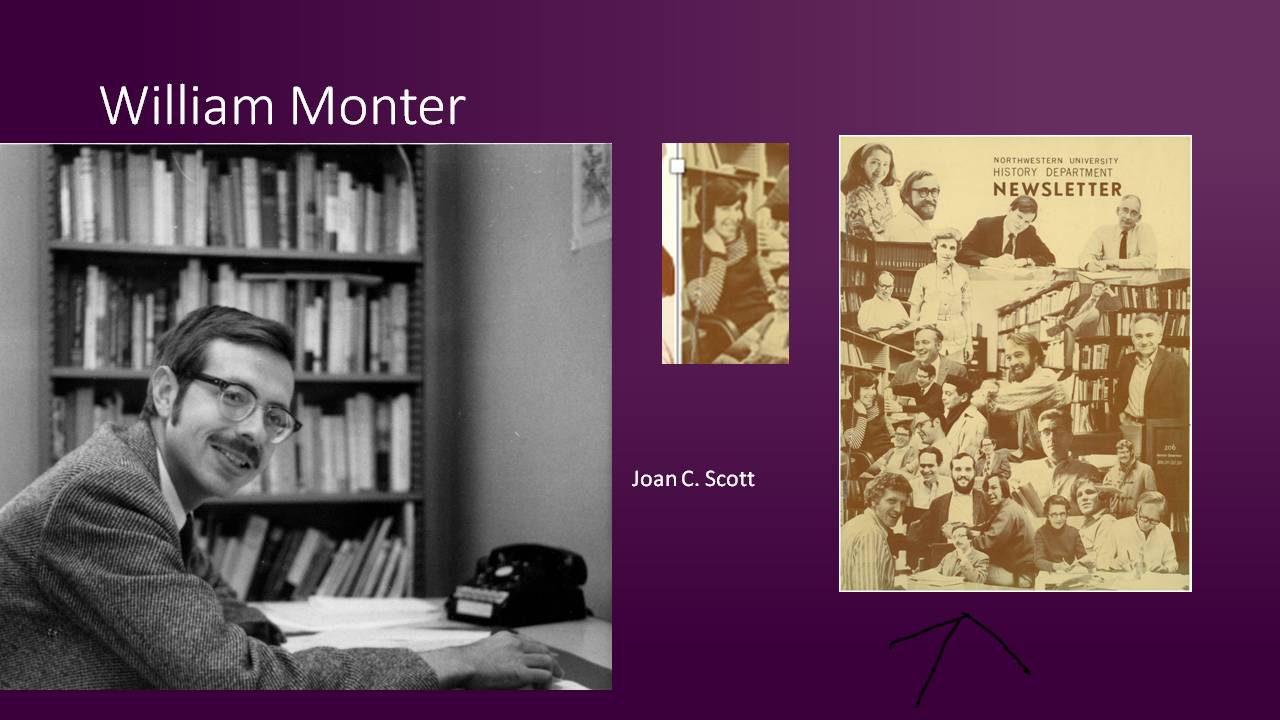

Northwestern, somewhat improbably, was also home to two pioneers in gender history in the 1970s: Bill Monter who had a long career here, including publishing his pathbreaking work on witches in Early Modern Europe, and Joan W. Scott who was briefly at Northwestern (1972-74) before moving on to more hospitable environments.

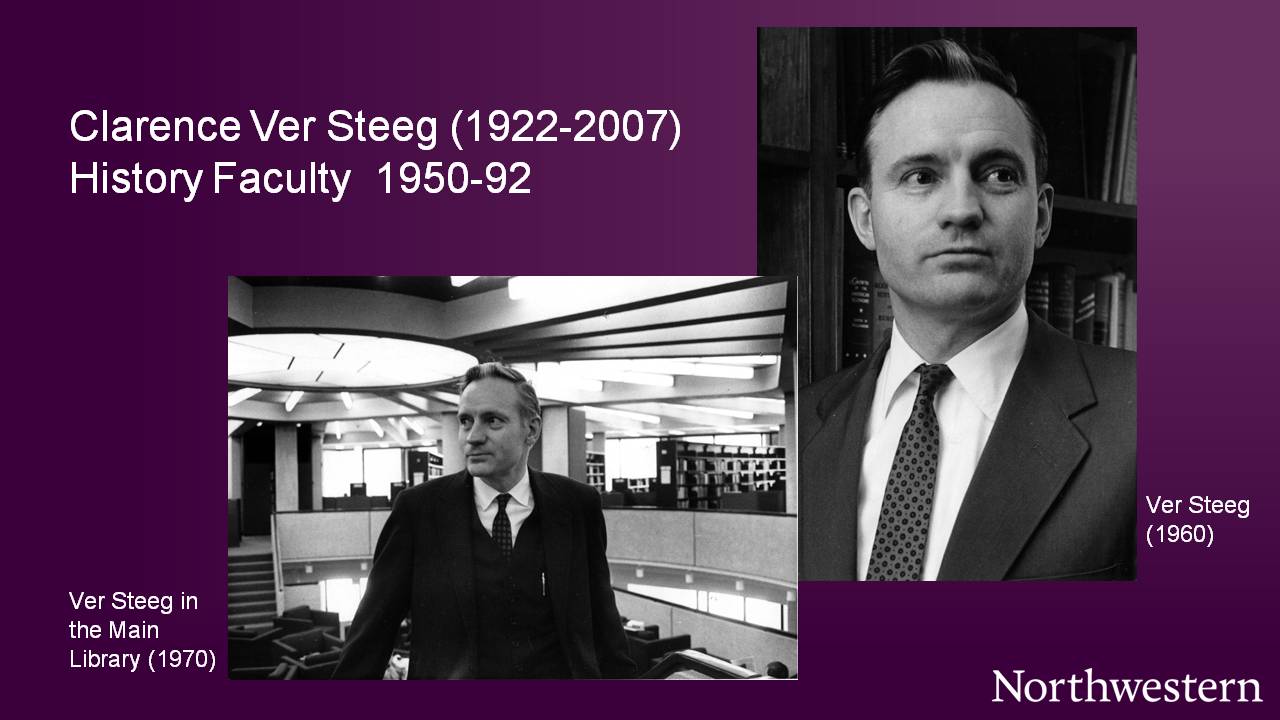

Historians made their mark on Northwestern in other ways as well: In 1969 the History Department invented what are now called First-Year Seminars “to encourage history majors to be more engaged and les passive.”[1] They remain a mainstay of the student body’s first year experience. Professor Clarence Ver Steeg, who started at Northwestern in 1950, chaired the committee that planned the University Library which opened in 1970. He was also part of a comprehensive examination of the undergraduate experience at Northwestern in 1968 and 1969 in a report officially entitled “Community of Scholars,” that sought to create a genuine community of scholars, because that formation “would best be able to inculcate the key qualities of an educated person—competency, general education, and civility.” We are still working on that one. Bill Heyck took on all aspects of student life in the 1980s. That meant recommending major changes in the college pedagogy and intellectual life outside the classroom. His group, among other things, also expanded the residential college system, which began in 1972 with five thematic dorms, and is still housing students today.

And this reckoning introduces a sad note because, since that alumni event in October, we lost a colleague who had been here since 1961, Jock McLane. Jock was the last of the professors of the 1969-70 era to retire from Northwestern and remained an active member of the community even after he did so. Please see the obituary elsewhere in this newsletter.

The other members of the 1969-70 department were Robert Bezucha, Gray Boyce, T.H. Breen, George Daniels, Christopher Lasch, Robert Lerner, George Romani, Frank Safford, Franklin Scott, James Sheehan, James Sheridan, and Robert Wiebe. Photographs of all of them are below.

Laura Hein, Chair, History Department

[1] “What students studied and why” William N. Haarlow, Crosscurrents-archive, 2008 NU website.