In Memoriam: Raymond Foster Kierstead (1934-2023)

In Memoriam: Raymond Foster Kierstead (1934-2023)

Dear colleagues,

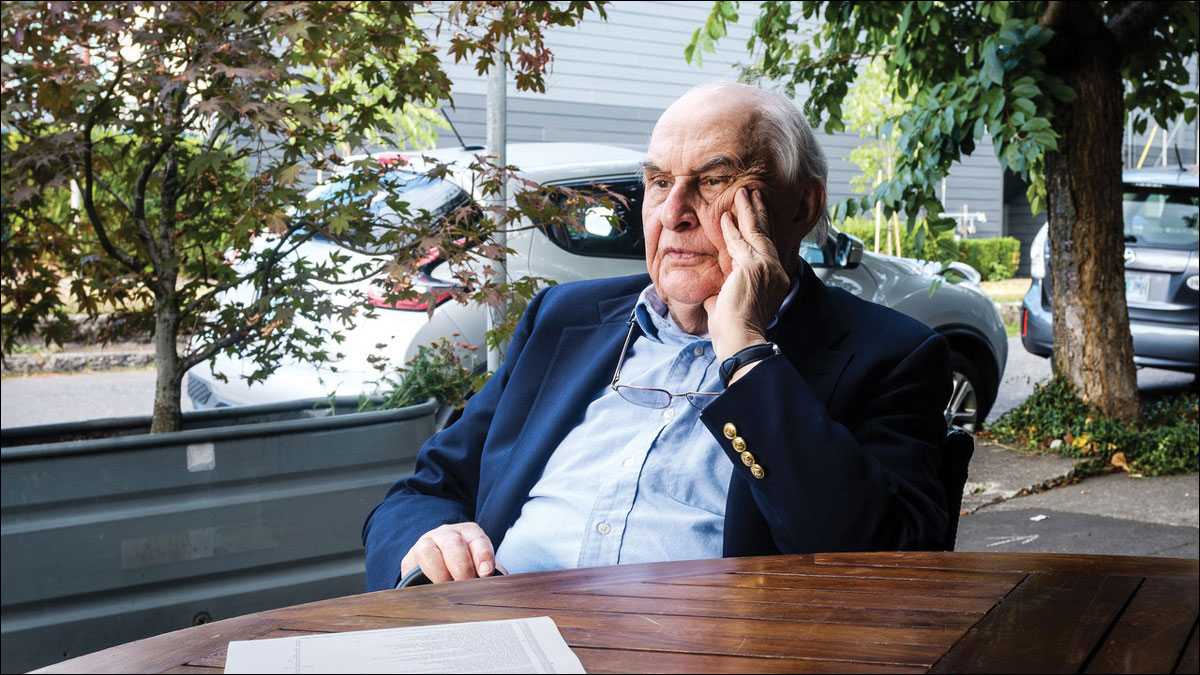

With equal parts sadness and affection, we write to announce that Raymond Foster Kierstead, Jr., Richard F. Scholtz Professor of History and Humanities Emeritus at Reed College, passed away on September 13, 2023, in Portland, Oregon, with his devoted family by his side.

Born in Portland, Maine on August 31, 1934, Ray attended Bowdoin College, graduating summa cum laude in 1956. After a formative Fulbright year in Paris, he returned to the United States and enrolled in Northwestern University as a graduate student specializing in French history. It was in the history seminar for first-year graduate students that Ray met Marilyn, his wife of 65 years. He received his M.A. and Ph.D. from Northwestern University in 1959 and 1964.

Following his time at Northwestern, Ray taught French History at Yale University, the University of Texas at Austin, Catholic University of America, and finally, in 1978, he took a permanent position at Reed College where, in 1993, he was named the Richard F. Scholtz Professor of History and Humanities in recognition of his intellectual leadership. Ray was the author of one monograph, derived from his dissertation, titled Pomponne de Bellièvre: A Study of the King’s Men in the Age of Henry IV (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968). Working with his wife Marilyn as co-translator, Ray also edited and translated an important collection of essays by other historians, published as State and Society in Seventeenth-Century France (New York: New Viewpoints, 1975).

Ray’s long standing desire to teach at a liberal arts college similar to Bowdoin meant that he quickly felt at home at Reed and with its students. His courses on early modern French history, with a special interest in social and cultural history, soon became legendary and he was also an integral part of Reed’s unique humanities program, helping to guide its evolution and reveling in the pedagogical opportunities it afforded. Ray was a gracious, unpretentious man with deeply embedded Maine roots and the accent to go with them. Although a serious scholar of early modern France, Ray’s greatest pleasure was as a teacher.

Over his twenty-two years at Reed, Ray made a profound impression on numerous undergraduates. One former student, now a professor of American history, recalls that from the beginning, “Ray was a brilliant and funny teacher—there was never a dull moment in his classes, no matter how many dull students turned up.” Many other former students of Ray’s also attest to his keen intellect, his excellent sense of humor, and above all else his kindness, generosity, and openness to working with everyone, even the “clueless freshmen” who occasionally blundered into his upper-level history classes. His challenging courses were a high point for many students at Reed, and inspired quite a few to major in history and in a number of cases (including one of the authors of this text) to eventually become professional historians themselves. Ray could be profound in the classroom—a former student reports that he is still grappling 25 years later with Ray’s observation that “the function of ideology is to conceal reality.” Ray could just as easily be funny: in a 2004 lecture on Apuleius’ comedy The Golden Ass, Ray brought down the house when he only half-jokingly observed, “Food is far more interesting, and not as complicated, as sex.”

Ray’s advanced courses on the Annales School, the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, and early modern family history were many Reed students’ “profound, fiery introduction to really doing history” (in the words of former advisee Brett M. Rogers), as well as their first exposure to a bookcase’s worth of great historians of early modern France, including Marc Bloch, Fernand Braudel, Richard Cobb, Robert Darnton, Natalie Zemon Davis, Georges Duby, Lucien Febvre, Lynn Hunt, Jacques Le Goff, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Mona Ozouf, George Rudé, and Albert Soboul, among others. While skeptical of modern social theorists such as Jürgen Habermas and Michel Foucault, Ray was more than willing to engage with their works when students expressed interest in them.

In a profile of Ray published in Reed Magazine (Aug. 2000), Patti MacRae wrote: “Ray Kierstead's love of teaching revolves around the belief that the acquisition of knowledge is part of becoming a civilized being and a thoughtful citizen. ‘Reed students are demanding,’ he once noted. ‘They have expectations, and making your teaching meaningful for them makes your own life exciting. We have an environment here where that can happen.’” Former Reed president Steven Koblick wrote, “For those of us who are dedicated to the life of the mind and to first-class undergraduate education, Ray Kierstead stands as a beacon of wisdom and thoughtful teaching.” In 2002, the Bowdoin College Alumni Association presented Ray with the Distinguished Educator Award.

Ray retired from Reed in 2000 but remained an active part of the Reed and Portland communities for years afterward., At Reed, he continued to lecture in the humanities program and maintained lively friendships with many of his former colleagues. A keen observer of humanity and its foibles, Ray’s wit, wry sense of humor, and wisdom made him a valued mentor and friend to many of the scholars and teachers who followed in his footsteps at Reed. Ray loved to talk about books and tell stories, doted on a series of beloved canine companions, and was known for his martinis and fine taste in local restaurants. Above all, he was utterly devoted to Marilyn and to their children and grandchildren.

Linda Lierheimer, another former student who is now herself a professor of French history, sums up the feelings expressed by many who passed through Ray’s classes or were fortunate to have Ray serve as their undergraduate advisor: “He was my mentor and had a huge influence on my life. He gave me my love of French history and was the reason I went to graduate school and became a professor and historian. I still think of him all the time. An amazing man, teacher, and scholar who, I like to think, lives on through all the students he mentored and taught.”

Ray Kierstead had a rare gift for using French history and historiography to inspire a multitude of people to think carefully and critically about the past, about how we today write about the past, and through conversational analysis to engage the present with joy and marvelous good humor. He will be remembered with great fondness by all who knew him.

From Julia Landweber & Michael P. Breen (he/him/his)